Chubut, Argentina. No to mining, yes to oil.

I recently spent almost three weeks in Chubut province. Home to a strict anti-mining legislation, gold and silver deposits and a large oil industry. How does that fit together? Let me explain.

With the name of my channel, my background as an economic geologist and a generally libertarian view of the economy, one would expect this to be a pro-mining article. It may be so. But I’ll try my best to explain the anti-mining sentiment. I think to be – first and foremost – intellectually honest but also to understand the other site and maybe solve problems/find a compromise, it is important to do so. Most information here was gathered rather randomly while stumbling into people during my travel. It is guaranteed to be *not* representative since it represents single, individual opinions. Nevertheless, I hope it can give you some insights into (practically) the last anti-mining province in Argentina. Adelante.

First, what is a Chubut? Chubut is one of Argentina’s Patagonian provinces. It is geographically characterized by the Peninsula Valdez, a hotspot for whale watching. The nearby city of Puerto Madryn is a famous destination for summer tourism due to its beach and sea life. It also hosts Argentina’s only aluminium smelter, operated by Aluar. If we follow the coast further south, the mouth of the Chubut river, settled with the province’s capital Rawson and as well as Trelew, comes next. What follows is a basically endless steppe of 400 km. The scenery here is exceptionally boring due to its flatness. Then, we reach Comodoro Rivadavia, Argentina’s oil capital. In 1907, oil was discovered here by a German guy called Josef/José Fuchs. This oil discovery was organized is a somewhat secretive way. Long story short, YPF (Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales), the countries (currently) state-owned oil company, was founded here in 1922. It was also the world’s first state-owned oil company globally. Comodoro is a relatively rich industrial city. The oil sector employs many people and pays well. About 1/3 of the Argentine oil production comes from the region (I guess it is a bit lower with Vaca Muerta taking off now). There is also lots of industry supplying the oil sector. However, the city lacks some colour and the constant winds can be quite annoying.

Land inwards, there is also a lot of steppe. Really, lots of it. After quite a bit of that, you reach the Andes. Most important places here are Esquel and Trevelin, like Puerto Madryn, Trelew, Rawson and a few other towns, they are Welsh foundations. In 1865, Welsh settlers landed at Madryn and with time and help from the local Tehuelche tribe, they reached the Andes after colonizing the Chubut River valley. The Welsh origins are still present in the area today, it is an accepted minority language and even Welsh schools and newspapers exist. You see many redheads, an usual sight in LatAm.

Chubut’s border is close to El Bolsón, the hiking and backpacker hotspot of the country. Generally, I have the impression that many people came to the area (especially the Andes chubutense, not so much Neuquén or the rest of Rio Negro/Bariloche) to escape big city life in the ciudad de la furia (Buenos Aires). There is the cliché that the region is full of hippies and I can say that without being in El Bolsón directly, I got that vibe, too. It appears that many people have developed a romantic view of the area. Which is understandable, it is an absolutely stunning place. But a bit of mining in the desert doesn’t alter that situation. But it could change their local culture if well-earning miners move to their towns and villages. Like it or not, but this is something I respect, and I can understand that fear. And when you see how some of the well-earning petroleum workers behave in Comodoro, you understand that fear even more.

Currently, about 600,000 people live in Chubut, resulting in a whopping population density of 2,7 people/km². That’s half of Australia’s. Comodoro has about 200,000 inhabitants, Trelew and Madry a 100,000 each and hence, the area outside the towns is practically empty. If you drive the 400 km from Comodoro to Rawson, you’ll see endless steppe. Nothing more. The steppe between the Andes and the coast is practically devoid of significant human population, except the village of Sarmiento and the Chubut River valley.

So what we have here is a province that has an established oil industry, is practically empty and has a rich mineral endowment of silver, gold, uranium and maybe more. If you already have the (quite dirty) oil industry, no one should have a problem with perhaps one or two, perhaps three mines, right? Mh.

Everything started in the very early 2000s when a Canadian company started to explore the Cordón Esquel (a mountain series) for gold – successfully. Plans to start a mine about 40 km north of the actual town of Esquel where presented – and the locals went straight to the barricades. The mine is not visible from the town, but a nearby ski area might be a bit impacted in its view, depending on the mining layout. Since the scenery offers a view of practically untouched nature, a bit of mining infrastructure might have a noticeable impact. The deposit is located stream-upward of a lagoon that supplies the town with water. Cyanide leaching was proposed to process the ore (epithermal low sulfidation for the fellow geo-nerds) and an open pit design was presented. Admittedly, this is not really low-impact. Now, an underground mine is in the latest stage of planning, but it is generally difficult to find any new information on the project.

I don’t know how the company behaved itself, how it all started, but – long story short – a plebiscite was organized in 2003 and 82% of the population voted against the project. I have to say that from personal experience with such things, I like this base-democratic approach. Because in my case, it was never clear whether you’re dealing with 5 loudmouths or with a majority being against you. A plebiscite clarifies that.

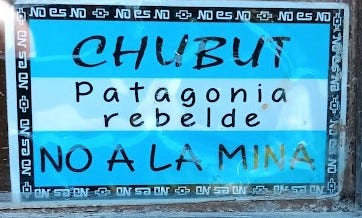

On the cultural site, being anti-mining became like the local/provincial religion. On every 4th of each month, a rally is held in the town. You see “no a la mina”-slogans pretty much everywhere. On stores, walls, even in the landscape. And so it was with my Air-BnB. And in the front door of the house, this sticker greeted me:

Oh, well, this might get interesting, thought I. And right I was. The son of the family where I was about to stay let me in, we had a little chat, I went to my room. When I was leaving for a walk, I met the (quite attractive) daughter coming home from work. Nice chat with her, too. Told her I’m a geo, she was cool with it and told me that she has two friends who are in the sector was well and once they were hiking and found many cool things, etc. Okay. A bit lower tension. When I came back in the evening after having enjoyed another great bife, I was greeted by the family’s mother. An older lady, very friendly. And here it started. I came back maybe at 10 pm, and we chatted straight until 4 am. And got along greatly!

Besides all the “off-topic”, we talked about the obvious thing as well. I found out rather quickly that she was one of the organising heads behind the movement against the mine. And I have to say, I expected a more radical and less technically educated person. Not so sound arrogant, but most of the time when I’m talking to anti-mining folks, they seriously lack understanding of the technical aspects, hence come up with all sorts of irrelevant fears and claims. That is unfortunate because it really hinders a serious discussion and exchange of standpoints.

Local example: the recent wildfires. I heard from a few people that the fires were set intentionally and that miners were accused as one of the likely responsible. I explained to the older lady that I recently spent some time in Greece in an area affected by wildfires, and it was a mess because all the rocks were covered with coal dust. All black. Not helpful. She understood. Others maybe (likely) don’t. She interestingly mentioned that the company owning the Suyai project (Pan American Silver after they bought the earlier owner) helped affected locals with some money. I asked whether that is a bad or good thing. She replied that it is a nice gesture, but on the other hand, it feels like you’re getting bought. And who likes that feeling?

She elaborated further on that, saying that she doesn’t like it that some foreigners/gringos come in and take their resources. And certainly, there are numerous examples of how this story ended bad for the locals. Want to be next in line? Not really. And while I can understand this feeling, I explained that in Argentina (and Germany… pretty much everywhere outside US/UK/AUS/CAN), you have not enough risked capital to conduct such programs, that even rich countries like Germany, Sweden, Norway, rely on foreign capital to conduct exploration. And with the “nearby” example of Santa Cruz, where 7 active gold-silver mines operate much to the benefit of the locals, I tried to explain that this foreign involvement doesn’t necessarily need to be bad. Not much resistant from her side, but she brought up the water problem.

And that is indeed a problem. Even with the best standards, you cannot guarantee that no accident affecting water quality will happen. Water consumption is also a (solvable) problem. Further, I figured out that the impact on the tourism sector did not play a role in the initial considerations against the project. Esquel – in contrast to El Bolsón or Bariloche – doesn’t attract much tourism, so this was no major fear. And if it was, I would demand from the company to implement a tourism program into their operations. Mine visits for interested people, a gold-mining theme park, etc. It would be unique, educating, and good for everyone. Just my thoughts here.

Let’s bring Navidad into the chat. Having identified that most of the resistance against the Suyai project stems from the fact that is just located unluckily, Navidad in the empty steppe should not have that problem. Well, it does.

In this case, we are not dealing with one of many gold-silver projects. Navidad is the second largest undeveloped silver resource on the planet. M&I resources are at a whopping 155 Mt grading 127 g/t silver. That makes 632 million silver onces. At current silver prices, we are talking about a worth of 16 billion USD in the ground. Over a mine life of at least 17 years, this would to a game changer for the province and calculations show it would actually solve most of the province’s (quite serious) financial problems. It is a deposit cropping out that the surface, forming a hill, so all you have to do is to mine that silver-rich galena hill and ship the ore to the next smelter. Simple.

The lady explained to me that Esquel’s movement has not a big issue with the Navidad project. They might not like it, but it is not really affecting them. Who is affected then? The coastal cities of Trelew and Rawson. Their fear is that the mine could affect a nearby aquifer, and that is bad for the water supply of these towns. I actually doubt that because there is not much water that can be affected around Navidad anyway and since Trelew and Rawson are located in the valley of the Chubut River, the river is most likely their main source of water. Navidad (unlike the Paso del Sapo prospect, for example) is far away from that river. So not a problem, let’s try it.

The last governor of Chubut wanted to repeal the law prohibiting open-pit mining. This resulted in widespread protest and a bunch of “activist” did quit a job of burning wheels in the streets. Nothing against peaceful protest, but burning stuff usually doesn’t give me the impression that you are open for discussion and compromises. What a drastic contrast to the civilized and pleasant conversation I had in Esquel.

The current governor, Nacho Torres, is against mining, too. This, however, didn’t stop him from to recently sign a publication together with all governors of the other Patagonian provinces that demands from Milei not to cut the 150 million USD paid by all Argentines to subsidize the Río Turbio coal mine in southernmost Santa Cruz. It also didn’t stop him from – to solve some debt issues that he has – threatening a stop of oil production (1/3 of the province’s GDP) to blackmail the national government. The oil companies promptly said they won’t play this game. Furthermore, YPF is about to leave Chubut. Drilling costs are increasing and Vaca Muerta in Neuquén province is more lucrative. After almost 120 years of oil extraction, reserves are low, and production cost are high after all.

On the other hand, a few comments from Buenos Aires that Chubut basically consist of guanacos walking through endless emptiness weren’t well received and sparked the creation of some rather funny memes. People feel once more badly treated by outsiders.

After explaining all of this, the question that arises is what the locals think. Navidad is located in the department of Gastre. 16,000 km² (half of Belgium), only 1,400 people living there. Population density: A stunning 0,09 per km². That is one in every 10 km²! Many people emigrate due to the lack of work, and I think I don’t have to explain that this place isn’t blessed with a vibrant economy. Logically, people there are in strong favour of the Navidad project, since it brings them work and stops emigration. But in the larger cities far away, no one wants to hear that. What a pity.

In summary, Chubut faces high debt, low economic activity and a potentially shrinking oil sector, which constitutes the largest share of the local economy. On the other hand, opening up to mining and making use of their huge potential – which is said to be larger than that of Santa Cruz! – could very well offset that and bring wealth to the province. But the fierce resistance of parts of its population makes this impossible for the moment.

Regarding Nacho Torres, he appears to me as a walking cliché to the Argentine political caste. I don’t know much about him. I understand that it’s not helpful for his career to be pro-mining. But blackmailing the national government with oil, being against productive, wealth-creating mining but in favour of unproductive, wealth-destroying mining. That doesn’t make me like this guy.

Anyway, it appears to me that the choice they have is the following:

Open up to mining or be poor!

I hope I could give you an insight of what is going on in Chubut and while I can understand the hesitation in Esquel, I hope that the Navidad project will find its way to production, providing the local population with well-paid jobs. Seeing the pictures of them hoping for a better future emotionally moved me a bit.

Thank you for reading!.

Another great article 👍