The Deseado Massif - Argentina's premier Gold-Silver District

The Argentine economy is bottoming, and so are gold-silver miners. Are the Argentine miners a contrarian's dream?

Most people probably have nether heard of this region. And there is good reason for it. The Deseado Massif, a highland area in the Patagonian Steppe in the Argentine province of Santa Cruz, is described pretty accurately as a barren and empty place not far away from the edge of the world. Tierra del Fuego is only 1000 km further south and, especially in winter, one feels that Antarctica is not too far away as well. A strong wind is blowing almost constantly, making it the dominant element here.

Not much need to go there, right? Well, not so fast.

First, the name is quite intriguing. Deseado in Spanish means ‘desired’, so one could imagine a story of gold at the end of the world, some pioneers searching for their big fortune in a remote place finally making their big find. I have to disappoint you. In 1586, Thomas Cavendish, an English explorer, landed here with his ship Desire, named the place Port Desire, which later turned into Puerto Deseado. Today, the town has about 10,000 inhabitants. That’s the rather boring history.

The area was formally annexed in the 1880s by the Argentine state after President Roca’s famous ‘Conquista del Desierto’ – the conquest of the desert. Some European immigrants, mostly Italians, Spanish, Germans and Poles, settled in that area living from sheep farming. In 1902, oil was found in Comodoro Rivadavia, just north of the Deseado Massif, and the region was practically left without any attention.

That changed in the late 1970s. In a remote quarry, barite was mined for the oil fields. Barite is a very heavy mineral used in drilling fluids as a weighting agent to regulate the pressure in the hole. These barite veins are hosted by volcanic rocks of the Chon Aike Formation, which stretches over most parts of the Deseado. Maybe it was pure coincidence, perhaps someone was curious because of the high gold prices at that time, perhaps some geologist had an idea, since barite is a common mineral in many gold veins. We only know the result: There is gold in these barite veins. Quite a bit, actually. Since 1998, this place has been known as the Cerro Vanguardia mine, which in 2022 produced 170 koz of gold and 3,7 Moz of silver. Quite a big boy.

The gold story in that area is surprisingly young and only really began in the early 1990s when Argentina opened itself to foreign mining investors under President Carlos Menem, a proto-Milei. Since then, many companies rushed into this place and got lucky. There are 6 producing mines today with numerous projects under exploration, development, or care & maintenance. Let’s have a closer look.

The Geology of the Deseado Massif

This wouldn’t be a proper article about mines written by a geo without the obligatory geology lesson:

Argentina can be divided very generally into two geological provinces: The Río de la Plata craton and all the microcontinents that smashed against it. A craton is a block of old, rigid continental crust and tectonically speaking, not much happens to it. The Río de la Plata craton is pretty much congruent with the plain Pampa – no tectonic activity, no mountains. Some 400 million years ago, a smaller continent collided with the craton and together, they formed a larger landmass. This continent comprises today’s Patagonia, and the metamorphic basement rocks of the area are witnesses of this collision.

Just like people, continents divorce, too. And so it happened that in the Jurassic, South America and Africa decided to go their own ways – resulting in the formation of a new ocean: the Atlantic. The child, Patagonia, stayed with South America but, of course, suffered during the divorce: An intense volcanism took place as a resulting of rifting in the east, subduction in the West and a loss of hot activity underground. Without going too deep into geology or making further divorce analogies, a huge magma reservoir formed under Patagonia, supplying the numerous of the material we find now at the surface. Due to special conditions in the crust, the volcanism here was acidic and not mafic, that means the silica content is higher than usual. Think of granite (or rather rhyolite, granite’s volcanic twin) instead of basalt. Acidic volcanic eruptions are very explosive. Good examples here would be Pompei, Mt. St. Helens or the Krakatoa. Hawaii, as a basaltic example, is relatively silent and constant in comparison. The remnants of all these explosive eruptions can still be found in the whole area in form of ignimbrites, lava domes, tuff and so on. They can be found even in Antarctica.

Everything would be nice and fine if the geological history stopped here, but thanks to some younger sediments and widespread basaltic volcanism, only on about 1/3 of the massif’s surface, the right rocks (purple in the map) are outcropping at the surface.

Map 1: Geological map of the Deseado Massif, showing mining and exploration projects of all stages.

Back to precious metals: Now, all this hot volcanic material lies around, and groundwater (or rather steam) penetrates the rocks and leaches gold, silver, and some base metals out of it. Due to the rifting and the opening of the Atlantic Ocean, the tectonic setting is just right so that faults (=large cracks) form and the hot fluid finds a way to rise to the surface. By doing so, it cools down, starts to boil, changes its chemical properties, etc. And this is the right procedure to form a so-called low sulphidation vein. The fluid cannot hold the metals any longer, and the veins get filled with minerals. Like when boiling salt water in a pot forms salt crystals – basically the same process.

Sample of gold-rich quartz vein. The gold here is located in the darker parts, which contain iron oxide (specularite/hematite to be precise). Since there are no sulphides here, this material is suitable for leaching.

The upper ends of these ~140 million years old systems can still be found at some places. Just like in similar currently active hydrothermal systems, the sediments of hot springs like sinters or travertines lie around there in the steppe. During my last trip to Bariloche (far away from the Deseado) I found exactly that while randomly hiking. Jurassic Park for geologists, quite literally.

A block with a vein. Again, we see mostly quartz and iron oxide with some open cavities all some nice textures. Other parts of this vein contain lots of sulphides which are rich in silver, so this material needs to be floated to produce a Au-Ag concentrate. Vein width is about 20 cm.

Mining Economics & Techniques

The typical vein in the Deseado can be described as a few decimeters to meters thick and a couple of hundred meters long, the depth is mostly unknown, but some drill intercepts are from a few hundred meters. Drilling deeper makes not much sense in most projects now, since it’s expensive. For example, Cerro Vanguardia operates several open pits, so if possible, new resources are best found laterally. Nevertheless, where economic, underground operations take place.

Most reserves have gold or gold equivalents of 1-2 g/t on the lower end, but it can be higher. What I like about these deposits is the chance to encounter ore shoots, where a thicker zone of the vein is intercepted that usually has fairly high grades as well. Several hundred g/t Au are in the cards here. I’ll give an example further below.

Most mining operations in the region start with a simple open pit design. The veins are usually found as an outcrop at the surface and obviously, you go for the easy stuff first. The cut-off you can expect here is low, and some companies give 0.3 - 0.5 g/t Au or AuEq for their operations. That makes good economics for an open pit mine. Since most veins are steep and deep, the necessity of underground mining arises eventually. This means less host rock needs to be moved to get the good stuff, but getting it is more expensive, raising the cut-off grade.

In terms of processing, two methods are used in the region. Especially towards the edges of the massif, the deposits tend to be richer in silver, which comes with elevated sulphide contents in the ore. In this case, standard flotation is used to produce concentrates that are sold as final product. In the other, classical ‘low sulphidation’ case, sulphides may carry the gold, but occur in much fewer quantities. Here, cyanide leaching is the way to go. Free gold is common as well and is often associated with the bonanza-grade parts of the deposits. Unfortunately, the concentrates and doré need to be exported via Puerto San Julian since no smelter/refiner exists in Argentina (business opportunity?).

Close view of a vein sample with bonanza grades. You can see the millimetre-sized gold flakes in the vein. The grade here is easily in the triple digits, or a few hundred times above the cut-off.

Production costs in the area (which fluctuated quite a bit during the year, generally topping in Q2), are as follows:

The Argentina Factor

As I described in my first article here, the current fiscal situation in Argentina is a nightmare for exporters (and importers) and one can only hope that Milei gets that problem solved. The current capital controls, artificial peso ratios and the (hyper) inflation make it not easy for the companies. Imports are expensive and needed to be authorized until very recently manually (!) by a central bank bureaucrat. Exports, on the other hand, suffered because of the artificially low Peso (~370 ARS/USD) while the unofficial rate reached 1000. In December, Milei devalued the Peso to 800. That helped exporters, but really sucks for Argentine savers. In more detail, special exchange ratios for miners exist, just like they do in about 20 other cases. This helps, but still, it is a huge clusterfuck of capital controls.

I just checked the current rates, and it smells like hyperinflation territory to me, even though inflation rises slower as before. So we will have to see how this develops. That makes my next holiday cheaper, but I honestly feel for the Argentines. For the miners, it’s not much easier. Import and export taxes, exchange ratios and inflation make life hard for them. High costs are not only a problem for Argentine producers, but in this case, they come on top of the local problems. And I think here lies the opportunity.

I like to buy miners or explorers when they lie beaten-up on the floor. With a global and a local factor, most miners active in the Deseado get beaten up from two sides. This depresses share prices dramatically and pushes companies to the limit. With the new government aware of these problems, one can expect that many of the local factors get removed from the scene in the mid-term. Milei wants to liberalize capital flows and facilitate imports and exports. On the global side of things, there are many reasons to expect a further rise in gold prices.

In this optimal scenario, both breaks could be lifted at more or less the same time, resulting in these companies going from really bad to just bad. And this usually the most fun part, albeit the most risky as well. From with normal level that can be expected, a further rise during a bull market can be expected. So I think we are bottom fishing here.

Stock pick - Cerrado Gold

There are obviously several companies active here. I focus on the company with the largest footprint in the area: Cerrado Gold (TSXV: CERT). Of course, this is no investment advice, it is just me blurping out vaguely plausible opinions with some maps. These companies are really cheap now and there may be reasons for this not mentioned in the article, so please do your own research. My approach here is a high risk/high reward thing, so please keep that in mind. Currently, I am a shareholder of Cerrado Gold, average price 0.78 CAD. Ouch, yes. I will add to the position when (I think that) the knife hit the ground. The current 0.25-0.30 CAD level looks good to me. I’m also no expert on companies’ finances, so if you see some major red flags here, please write it in the comments.

I’m sure there are other companies and projects there that are worth mentioning, but I like to focus on this one since they already have mines in places, a strong growth potential but suffer currently under the capital restriction and the general downtrend in the sector. Hence, the likelihood of them going bankrupt is limited and, IF the situation improves (especially in terms of ‘local problems’), they have a lot of upside potential. Patagonia Gold is in a similar situation.

Oother explorers active in the area are Unico Silver, advancing the Pingüino Project (which is an indium-rich polymetallic vein system, very interesting) and Mirasol Resources with several exploration projects. But to keep this article at a reasonable length, I focus on Cerrado only.

Cerrado Gold

Cerrado currently operates Minera Don Nicolás, a fully owned subsidiary and holder of the largest land package in the area. At a share price of currently about 0.27 CAD and with ~97 million shares outstanding, it has a market cap of ~27 million CAD. Besides their Argentinian projects, they advance another gold project in Brazil, which is planned to start production in 2025.

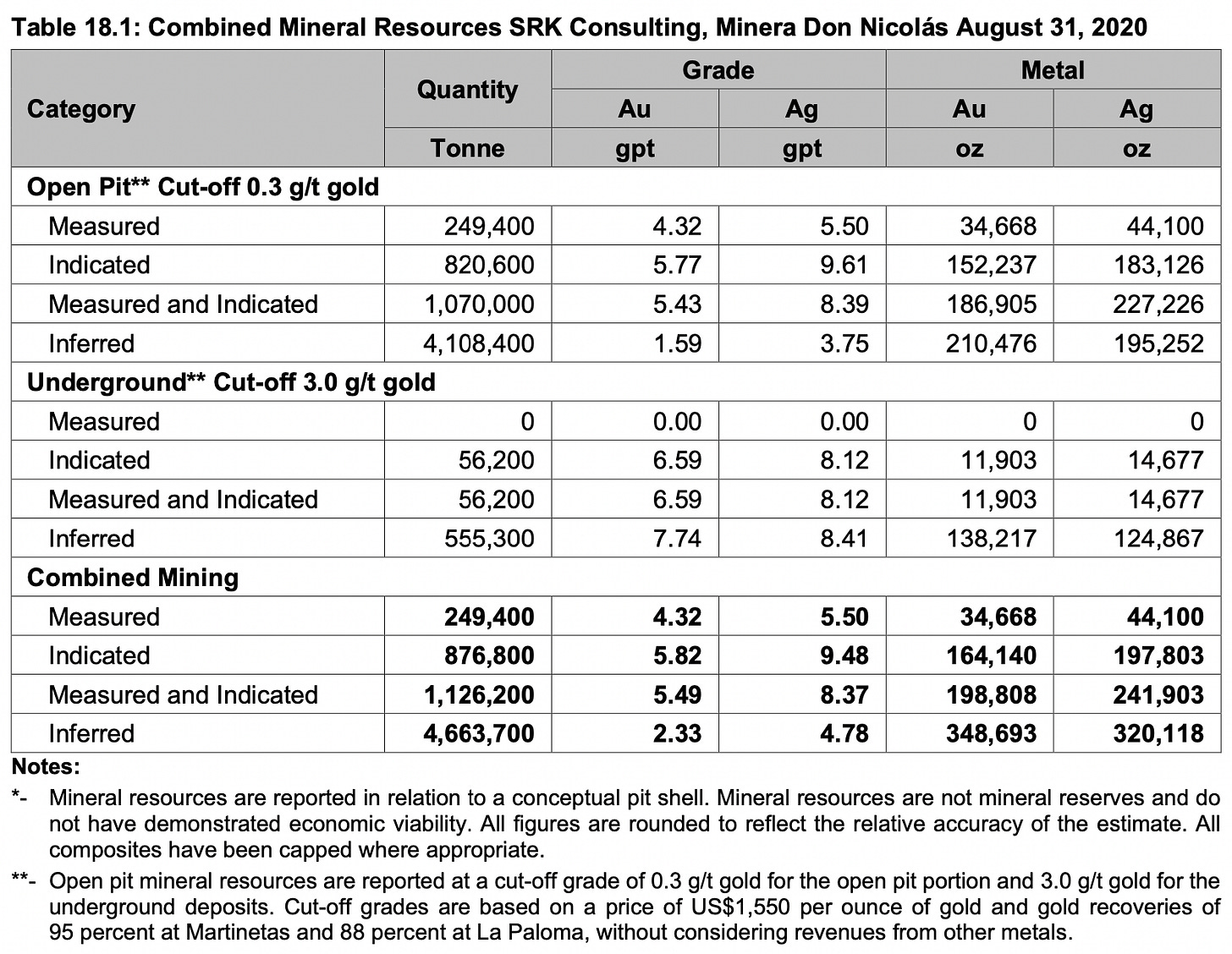

Minera Don Nicolás operates several deposits in their 333,000 ha concession and produced 54 koz gold last year and 80 koz is targeted for 2025. Every deposit has significant exploration potential. The ore is milled in a central plant and leached. Currently, the leaching process in Calandrias is starting, and at Calandrias Norte a higher-grade ore zone has been accessed recently. Currently, all operations are open pits with a cut-off at 0.3 g/t Au. Underground mining is currently planned at the Paloma pit. The reserves are as follows (Source):

Recently, their share price really got beaten due to the usual harsh winter conditions (I think it was rain followed by cold, so everything froze), production was lower than expected and the AISC cost rose from 1318 to 1703 USD/oz in Q3, also due to higher input costs. But the increasing inflation pushes prices up as well, and that has a negative impact on the finances of the company. Nevertheless, Cerrado is still the lowest-cost producer in the Deseado.

Unusual harsh winter conditions: Snow and temperatures of -20°C/0°F are things that happen there. Yes, South America has snow, that surprises people sometimes.

Production increased already from 11,4 to 15,6 koz quarterly, so things seem to be improving. Extra upside is provided by their Brazilian Monte do Camo project which - if in production - could lift the companies total production to 150 koz. Based on the low valuation, a clear path to growth and relatively low production costs and lots of exploration potential, I really like the company, especially at this stupidly cheap price. Mark Brennan, the CEO, has a lot of experience advancing projects in Latin America.

The next article will not be Argentina-related. It will most likely be about the emerging tin story, explaining tin geology, mining and processing. I have both scientific and professional experience in tin mining, so I think this will be good. Looking forward to seeing you there.

Cheers,

Geocap