Argentine Copper - Beyond San Juan

Let's talk about Argentine copper. Since San Juan is a well-known player in copper exploration now, I show which province could be the next copper hot spot in Argentina.

If you have a look where most of the world’s copper is mined (Chile & Peru), you will likely eventually ask yourself why Argentina - sharing 3500 km of the Andes with Chile - has not a single producing copper mine. That is even more surprising when you have a closer look at some Chilean mines, which are literally a stone throw away from the border. Does the geology stop at the border? Have the Argentines not been looking for copper? Did the kirchneristas steal it at all?

No te preocupes che, te voy a explicarlo.

As outlined in a previous article (Argentina’s Commodities - An Overview), Argentina comes with various mineral-bearing districts. In Patagonia, gold and silver mines dominate and the northwest of the country is part of the lithium triangle, the central part of the Argentinean Andes/Cordillera (that comprises the San Juan, Mendoza, La Rioja and Catamarca provinces) indeed has some very interesting copper projects. And it’s not only copper; it’s gold, silver, and molybdenum as well.

To understand the potential of the Argentinean side of the Cordillera (please pronounce it as Cordishera when in Argentina, thank me later), let’s have a look into the cooking book of geology and open the page of the receipt for nice porphyry copper deposits (PCDs).

Oceans, Mountains & Volcanoes: The Making of Copper Porphyries

In my studies, I learned that geology doesn’t end at political borders. Sometimes, maps can give you that impression when geologists from one administrative unit don’t talk to their colleagues on the other side. But that’s all to it, I cannot think on a single example where a geological border coincides with a political one. And so it is the case with the border between Chile and Argentina, stretching 3500 km through the southern Andes.

Chile is currently producing about a quarter of the world’s copper, and that huge endowment is easily explained when we look at the tectonic environments in which porphyry copper deposits form. But since I am sure many of you aren’t familiar with the term porphyry, let’s explain that first:

A porphyry is a magmatic rock that consists of a fine-grained matrix and in which larger crystals occur. That’s basically it. How does it form? That’s also relatively simple: When a magma cools, some minerals form earlier than others. The contrast in grain sizes occurs when such a cooling magma in which some crystals already formed gets pushed up to shallower levels where the magma cools down further and faster. So the rest of the melt has no time to form large crystals and forms a fine-grained matrix that surrounds the larger crystals. The texture alone can give a geologist a lot of information, since each texture is a result of a process.

Example:

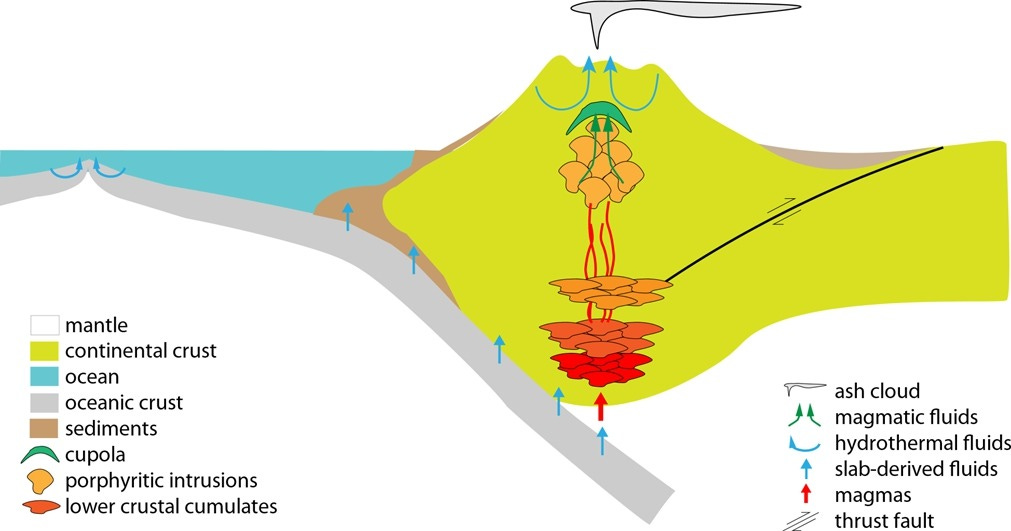

Now, what I described it just a common rock texture, got nothing to do with mineralizations. And yet, there is a special types of porphyries that are mineralized. What makes them special? [Plate tectonics has entered the chat]

PCDs are the most important source of copper and also molybdenum. Often, gold is associated with the copper, improving the economics of such deposits quite a bit. Therefore, these deposits are researched like nothing else. I want to keep it as simple as possible here. In short, there are several settings how these deposits can form and depending on the input factors, we have either copper-gold (Cu-Au), copper-molybdenum (Cu-Mo) or sometimes, all three occur together. Usually, on top of the porphyry system, there in an epithermal (Au-)Ag-Zn-Pb system. Often, these form nice silver deposits.

But what really makes PCDs great is the thick continental crust. How do we get that? A flat subduction angle! Usually, like the image shown above, the angle of subduction is around 30°. This means the oceanic crust has a relatively short period of time to get melted and release its metals. In the case of the Central Andes, more precisely between southern Peru all the way down to the just south of the Santiago-Mendoza line, we are dealing with a relatively flat subduction angle (10-15°) and this gives the oceanic crust just much more time to release its spicy copper, gold and molybdenum.

I think by now, without going much deeper into geology for now, you have an understanding of the large potential of the Argentine copper story. If that is all so easy to understand and rather obvious, then why is Argentina so underdeveloped in that regard?

Argentina’s Mining History

To answer that question, we need to have a look into the history of Argentina. The land is named after silver (latin: argentum), but contrary to what one might think, mining never really played a big role in the country. Sure, in the Spanish Viceroyalty of La Plata, comprising today’s Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, Uruguay and Chile, the Cerro Rico de Potosí was a huge silver mine and financed Spain’s colonial adventures. But it is in Bolivia now. Argentina never had big mines. Some minor gold and base metal mines existed here and there, but nothing that compares to Chile or Bolivia.

Why is that? Well, difficult to answer. I think, Argentina never focussed much on mining since the agricultural and the industrial sectors had a greater importance than developing the few deposits known at, say, the beginning of the 20th century. Historically, Argentina lacked big deposits of coal and iron to produce its own steel needed to build a heavy industry, but gold or copper never really have been a big issue. Another point that is critical is that most of the now known deposits and mineralizations in Argentina are covered by sediments and volcanics, whereas in Chile, they were just easier to find because the level of erosion exposes them.

Another important factor is that Chile around ~1900 was much poorer than Argentina and needed the money from the mining sector, and hence had an intention to look for more deposits - and they found them. To this day, exporting copper is the largest source of export revenues for Chile - about 50% of the total export volume. When General Pinochet re-privatized the Chilean economy after Allende’s socialist experiment in the 1970s, the nationalization of the copper mines was not undone, no, 10% of the profit of CODELCO, the national copper miner, goes direct to the military.

Around the time of Allende and Pinochet, Argentina started its economic decay: One golpe de estado (coup d’etat) followed the other, Peron’s reforms (introduced as early as the 1940s) lead to rising government spending, high inflation, low productivity and this didn’t make Argentina a place where you want to build a big copper mine. And if you had liked to do that, you just weren’t allowed: Investment in mining was closed to foreign capital until president Menem (the best one Argentina ever had if you ask Milei) changed the mining code in the early 1990s.

What followed was a lot of attention to the Deseado Massif (read more here) and its gold and silver mines. So it worked, foreign investment was attracted. While some exploration took place in the Cordillera, it didn’t gain the necessary attention to bring something into production. Another factor may have been that copper just wasn’t that interesting at that time. Since the 1980s, leaching of low-grade copper ore became economic and depressed prices significantly. And why look for copper in Argentina when there are other places with an established mining industry, like Chile or Peru? I think many companies just didn’t see it as a great opportunity at that time. The increasingly kleptocratic kirchnerist policies in the 2010s didn’t help much either.

Recent changes

If the title of the article caught your attention, you likely have noticed that Argentina got a new cool libertarian president cleaning up the socialist mess and that the world is also facing a problem with the copper supply. Add one thing to the other, and Argentina suddenly becomes very interesting to look for copper. Places like Santa Cruz, Salta and, of course, San Juan are constantly populating the upper positions in the mining jurisdictions ranking by the Fraser institute. In 2023, San Juan was the best jurisdiction in Latin America, and No. 19 globally between Montana/USA and Yukon/Canada.

But there is more to the story: Mendoza, just south of San Juan, and producer of the world’s best wines (author’s completely neutral opinion) for a long time prohibited any exploration and mining. Why? Because they feared that mining could negatively impact the water quality and since the vineyards are all artificially irrigated with water coming from the Cordillera, that fear is somewhat understandable. Marketing is another aspect.

But recently, the province changed its laws and wants actually to become a leader in green mining. As long as you can prove that your activity doesn’t harm any aquifer, you’re good to go. Unlike Chubut, a very special case as I outlined in a previous article, Mendoza wants to attract mining investments. I like that. And as shown in the geology chapter, Mendoza has some serious potential indeed.

Another aspect that hindered a pro-mining attitude was that the owners of the vineyards feared competition in the labour market. Guess where an unskilled labourer makes more? Picking grapes or driving a truck in a mine? But that resistance doesn’t seem to be that important any more and wine exports are actually not that important for Mendoza’s economy, since it has an industrial base that generates much more export volume.

San Juan, for example does not have an industrial base and currently, 70% of the province’s works are employed by the state. Seventy percent! The same goes for La Rioja, another former anti-mining province. But this province is in deep financial problems and recently issued its own funny money to pay its employees. With Milei cutting the funding of the provinces, places like La Rioja need to attract capital to create jobs in the private sector and generate tax revenue. Otherwise, the local governor will have problems financing his luxurious lifestyle, among other problems of greater importance. I like that dynamic. Pain where pain is needed. We should do this in Germany, too (Hallo Berlin!).

And now comes the big thing:

El Pacto del Mayo

In March, Milei announced that he wants to sign a new social contract for the country, involving the provinces. This pact comprises the 10 following commandments.. eh.. points:

1. The inviolability of private property.

2. A non-negotiable fiscal balance.

3. The reduction of public spending to historical levels, around 25% of the Gross Domestic Product.

4. A tax reform that reduces the tax burden, simplifies the lives of Argentines and promotes trade.

5. A rediscussion of the federal tax sharing to provinces, to put an end to the current extortionist model.

6. A commitment of the provinces to advance the use of the country's natural resources.

7. A modern labour reform that promotes formal employment.

8. A pension reform that gives sustainability to the system, respects those who contributed and allows, those who prefer it, to subscribe to a private retirement system.

9. A structural political reform that changes the current system and realigns the interests of the representatives with the represented.

10. The opening to international trade, so that Argentina becomes a protagonist of the global market again.

After reading this, the words that come to my mind are simple, but clear: Viva la libertad, carajo!

I think it is obvious that, if this pact gets signed on the 25th May, it would be historic: The 25th May 1810 was the day when the first local government, la primera junta, took office in Buenos Aires after the May Revolution, marking the path towards independence. Milei made it clear with this historic name and date, that the epoch of decadence is now over and a new - hopefully prosperous - chapter will be added to Argentina’s history. Will the provinces play along? We will see. But rest assured that if they don’t play along, they won’t see a single peso from Buenos Aires. Bad news for the governments of Chubut and La Rioja.

Milei has the right provinces by the balls and the wealthier provinces like Mendoza, Córdoba and San Luís support it. This makes No. 6 even more interesting since the latter two have laws in place that prohibit exploration and exploitation of metals. Do they have an interesting geology? Oh yes, they absolutely do:

Mendoza - the next San Juan?

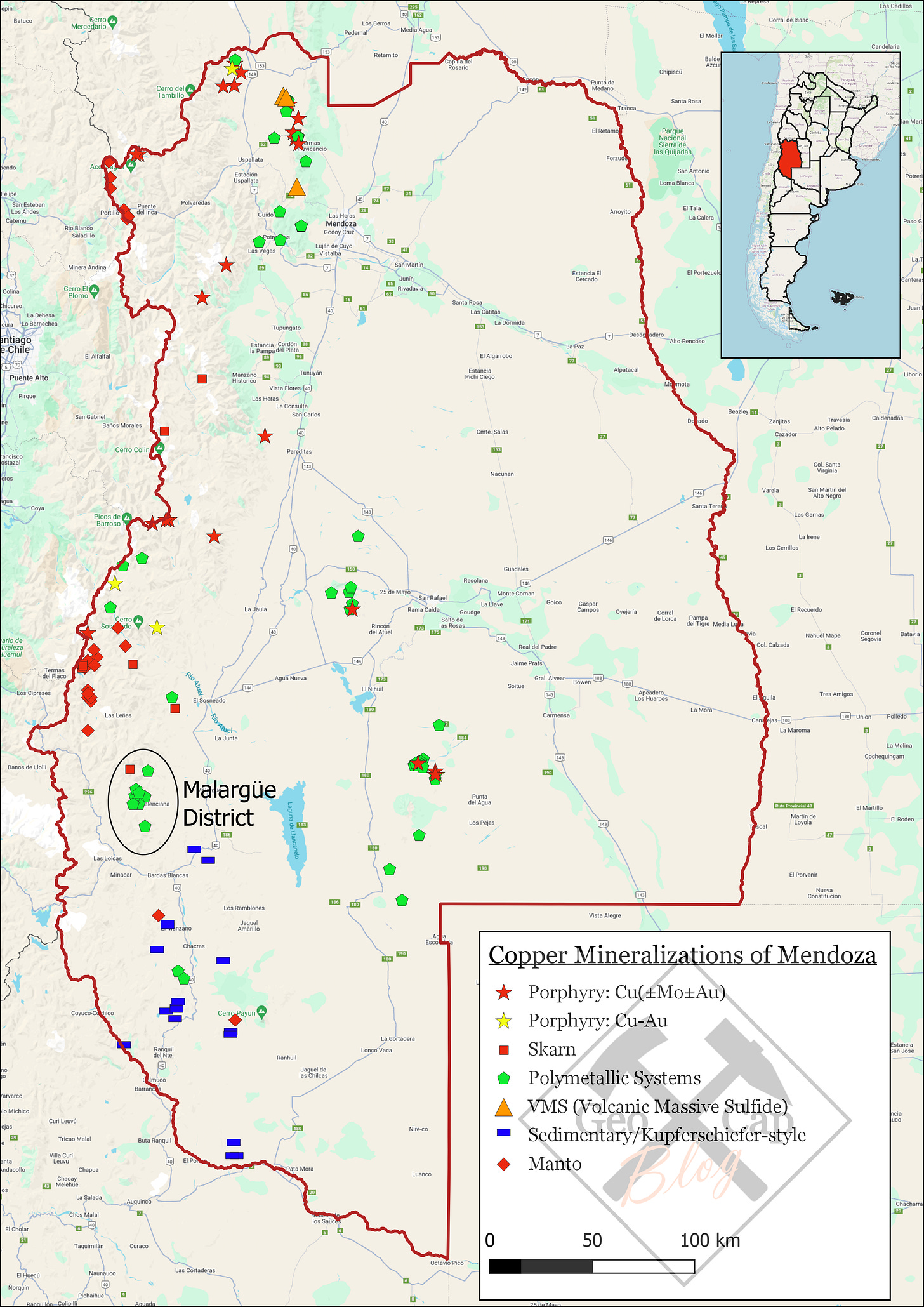

recently wrote an article with detailed overviews about the most interesting mining projects in San Juan. Check it out, I could not have done it better. But I want to go a bit further and present what the future of mineral exploration for copper could look like in Argentina. While I do not doubt for a second that much more copper still waits to be discovered under the surface of San Juan, Mendoza offers some known mineralizations that never got much attention because nobody was allowed to do something with them. Until now. I checked the online database of mineralizations of the Geological Survey (Servicio Geológico Minero Argentino - SEGEMAR). This is an excellent tool and source of information and, believe me, I killed successfully some evenings playing around with that thing. I filtered out all mineralizations in Mendoza and selected all deposit types that contain copper. Here is the result:

Let’s talk about that map (click on it for more detail). So, the porphyries are there and most of them are as expected close to the Chilean border, but not all. What is interesting to me is that there are clusters of the green polymetallic systems (mostly Cu-Zn-Ag-Pb-rich veins) are sometimes spatially associated to a porphyry. That makes sense because these veins are the hydrothermal part of the porphyry system. A distal part of the deposit, so to speak. But in other cases, there is no porphyry. But to form a hydrothermal system, you need a heat source, usually a magmatic intrusion, i.e. a porphyry. Maybe one should drill and see whether there is a shy porphyry hidden?

The Skarns and Mantos are stratabound mineralizations directly associated with magmatic intrusion. The magmatic fluids (= hot water vapour carrying metals) replace the original minerals in the sediments intruded by the magma and, as a consequence, metals precipitate. If a limestone is replaced, it’s a skarn, and a manto is a more general term commonly used in Latin America. In the end, these are very similar styles of mineralization. Skarn are generally closer to the causative intrusion.

Another eye-catcher for me are the Kupferschiefer-style sedimentary mineralizations. Very recently, these systems have been found in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru and they formed in the “shadow” of the Andes. The term Kupferschiefer is German and literally means copper schist. Large deposits exist in Poland and are mined by KGHM (huge mines, with lots of silver being produced as well). The African Copper belt (DRC, Zambia) is a similar story. These systems can be rather big, high grade and as in the Polish/German case contain lots of silver or in Africa, cobalt is associated with it. In the Mendoza case, the northern part of the Neuquén basin (which also hosts the Vaca Muerta formation) seems to be mineralized and that maybe means that larger parts of this basin are mineralized, similar to the German and Polish deposits.

Am I the first to find that out? Nope. Wincul SA, an Argentine company, currently undertakes a drilling program at the Cerro Amarillo project. The Chinese Hanaq Group recently staked 20 claims in Mendoza around this area in Malargüe. And that is a good sign that the Chinese continue to invest in the country, despite all diplomatic issues between them and Milei. In this article from early March, the provincial mining director, Jerónimo Shantal, said he was in contact with First Quantum, Fortescue, Anglo American and Lundin at the PDAC, and they said they are interested in coming to Mendoza. So there is already some activity. But I think the parts barely started.

And what comes further south, in Patagonia? Well, the photo I showed above in from Neuquén province and even while hiking in Chubut, I found some interesting things. But the Patagonian Andes are mostly national parks (for a good reason) and the local population is not the best friend of mining. So even if there is something of economic value, getting a mine permitted would require great effort. However, there is some potential. Since there is no thickened continental crust south of Mendoza, one cannot expect huge deposits like in central Chile or San Juan. Nonetheless, that doesn’t mean that there are no economic deposits. The extra-Andean geology of Mendoza and Neuquén is rather complex, and I think that justifies some exploration projects.

So in summary, the Argentine copper story is larger as it is recently reported from the San Juan projects. This further improves Argentina’s position to be the country to bring a significant amount of copper mines online with the coming decades. If Milei is successful to implement his reforms, I see a bright future ahead.

If you enjoyed this article, please leave me a like and subscribe to my substack. Thank you!

This is excellent Hannes, your knowledge and research as a geo into Argentina is outstanding mate!

Great work!