Uranium in Argentina

Introduction to the Argentine nuclear sector, historic uranium mines, recent developments and a stock pick as the cherry on top. 🇦🇷 ⚒️ ☢️

Buen día!

In this article, I want to walk you through the uranium deposits of Argentina. I’ll give you an overview from a geological and historic perspective, and also introduce you to the fairly advanced nuclear sector of the country.

I think that nuclear energy may be crucial for Argentina: Not only provides it the country with cheap & reliable energy, but the higher the share of nuclear power, the lesser oil & gas is needed to produce electricity, leaving more for export. Therefore, the national uranium deposits, the nuclear plants already build and those planned may play a crucial role to supply the country with the necessary energy to rebuild its economy and to also create export opportunities.

El sector nuclear argentino

Let’s start first with the industrial aspects of this article. I assume most some of my readers are not aware that Argentina operates two nuclear power plants (NPPs) at the moment and was the first LatAm country to use nuclear energy. Today, three reactors are in operation: Atucha I+II and Embalse. The Atucha NPP is located to the west of Buenos Aires, whereas Embalse is in Córdoba in the centre of the country.

Nuclear energy supplied around 8 TWh of electric energy in 2022, around 5% of total production. In comparison, natural gas provided about 50% of energy and hydropower is second at 16%. Wind and oil come third at 10% each.

The nuclear sector has its origins in the 1940s and 1950s. I actually looked up how strong the German influence was here - it’s a very popular cliché, isn’t it? - and besides a guy with the name of Ronald Richter who promised president Perón to build a nuclear fusion reactor (he failed, surprisingly) there wasn’t much of a German accent to be heard around the nuclear research facilities. Unlike at NASA, where are guy named Wernher von Braun (totally American name), who absolutely did not build the V1 and V2 rockets during WW2, successfully brought the Americans to the moon. So no, no cool stories of German nuclear engineers disembarking submarines at Argentine beaches. The submarine guys got involved in other businesses…

The early Beginnings

While there are no mines in operation currently, that wasn’t always the case. When the Argentine government became interested in reactor technology in the late 1940s - Perón’s interest here was the peaceful use of nuclear energy to power the national economy - the need to find domestic uranium resources arose. Since Perón wanted to industrialize Argentina to become less dependent on imports, the economy would need massive amounts of energy. Coal was not really available in Argentina (besides the highly subsidized Río Turbio mine in southernmost Santa Cruz), so the prospect of finding another source of energy - besides oil - that is widely available within the country was a very lucrative one.

Since uranium at the time was only known from a few places, most notably the German-Czech Erzgebirge or the Belgian Congo, the Argentine geologists tapped a bit in the dark. Uranium mineralizations in Argentina, especially in the provinces of Córdoba and San Luís, were known since the late 19th century. The German scientist and entrepreneur Herrmann Avé Lallement described them in the area. But the geologists figured out rather quickly that these pegmatite-hosted mineralizations are too erratic to be mined for uranium. So they needed to find something else.

Uranium Geology Basics

And here geology enters the discussion. To find uranium, what do you need to know? Here is a short summary:

Uranium is a chemical element that occurs in many geological settings. That is due to its chemical properties: Under oxidizing conditions, uranium is a very mobile element and easily dissolved into the groundwater. It can be leached out of rocks and transported over long distances (x0 kms) until it precipitates and forms uranium mineralizations.

But ‘primary’ uranium mineralizations exist as well. Since the uranium atom is fairly large and does not likely form part of the usual rock-forming minerals, it is part of the group of “incompatible elements” which are mostly associated to late-stage granites/rhyolites or pegmatites. Other members of that team are, i.e, lithium, tin, tungsten, niobium or tantalum. A rhyolite is the volcanic equivalent to granite, like basalt and gabbro.

While some mineralized granites and pegmatites of economic importance exist, most uranium is actually mined from ‘secondary’ deposits. The leaching affects large quantities of rocks and concentrates the uranium in permeable rocks, most often in sandstones like it is the case in Kazakhstan, the world’s largest uranium producer, or in the Canadian Athabasca basin, the other big uranium district globally. Depending on how the precipitation of uranium works in detail, grades can be very high (few percent) or very low (triple digit ppm). Due to the leaching and reconcentration, a rock formation that host only minor amounts of uranium far from any economic relevance can form an economic deposit, if just enough rock volume is leached and the uranium is precipitated in a concentrated way.

Sometimes, ‘secondary’ deposits are also located in veins, when the host rock filled with uranium-rich waters is cracked by tectonic forces. The fluids run through these veins and when they mix with another fluid with different chemo-physical properties, the solubility of metals can change dramatically. Regarding uranium, the so-called 5-element-veins are formed which contain (to a varying degree) nickel, cobalt, bismuth, silver and uranium. Not every metal is always part of the group, there are distinct silver-, uranium or cobalt-enriched veins known globally. U grades in these veins can reach double-digit percent, meaning the veins are filly almost exclusively which pitchblende (UO2). But that’s the rare exception.

In Argentina, all of these types occur, but the sandstone-hosted secondary mineralizations are the most important by a fair margin.

Back to the topic…

In 1946, the Argentine prospectors found what they were looking for. In Mendoza, the mineralizations of Soberanía and Independencia (Sovereignity and Independence - you get the point) were discovered and a bit later in 1951, the nearby Papagayos deposit was found. Mining took place for a few years, but the rentability was low and only 4 t of uranium were extracted. But it was a start. The mine closed in 1955.

This decision was facilitated by the discovery of the Huemul deposit near Malargüe further south in Mendoza, which was put into production only three years later in 1955. In the same year, the Sierra Pintada deposit was discovered, which would result in the most important discovery.

In the early 1960s, Salta joined the uranium business with the Don Otto mine and several other smaller prospects were discovered. In 1964, the Argentine government decided to build the first nuclear power plant in Atucha, Buenos Aires province. Fundamental for this decision was the fact that the uranium supply for these planned reactors was met by domestic production.

Argentina Becomes a Nuclear Country

Between 1968 and 1974, Atucha I was built. What a time that was. Bringing a mine into production only a few years after discovery and building a NPP in only 6 years. Hyped by the success, the Embalse NPPs started construction and were finished in only seven years in 1983. This was done by both domestic and foreign companies such as Siemens-KMU and others. Yes, there was a time when Germany was a leading country in nuclear engineering…

This increase in demand lead to an increase in production. Another spicy and interesting factor was that the military dictatorship that was in power from 1976 to 1982 also worked on a nuclear arms program, so the uranium story became not only vital to energy production but was also of strategic importance.

The military Junta was removed from power after the Malvinas war was lost against the UK (and that was closer as you might think, but that’s another story) and the new democratic government shut down the nuclear arms program. But on the civil side of things, they continued the construction of the Atucha II reactor that started in 1981. This time, construction would take until 2014, a whopping 33 years.

With stable domestic demand for uranium, uranium mining was conducted mostly by the CNEA - Comisión Nacional de Energía Atómica, but some private companies played a role as well. The bulk of Argentinas uranium came from the Sierra Pintada district in Mendoza: From 1975 until 1995, 1643 t of uranium have been extracted here. The whole district west of San Rafeal hosts about 12,500 t U with an average grade of 0,09%, according to Lopez Canton (2022).

Under the free-market reforms of president Menem in the 1990s, many subsidies for the nuclear sector were cancelled and due to the opening of the former Soviet block at the end of the Cold War, uranium flooded the market and depressed prices. This killed the Argentine miners and ended the domestic uranium supply until today. Between 1952 and 1995, about 2500 t U were mined. To put this number into perspective: In 2022, about 50,000 t U were mined globally. Hence, Argentina’s historic production is nothing globally significant, but did its job of supplying the national industry.

To sum all this up, here is the map bringing all these infos together:

Nuclear Industries

But there’s more than just some minor uranium mines and a few reactors. Argentina actually possesses the whole package of a nuclear industry. Besides the two NPPs, there are:

6 research reactor, mostly in universities

4 particle accelerators

3 atomic research centres

1 heavy water plant

1 uranium purification plant

Until 2010 and between 2015-18, a uranium enrichment plant was in operation

Since the Argentine NPPs operate mostly with natural uranium, enrichment is not really necessary in large quantities. Fuel rods are assembled in the nuclear centre of Ezeiza, Buenos Aires (very close to the airport). The heavy water plant is located near the town of Neuquén and supplies the domestic reactor and has some extra capacity for future builds.

INVAP and CAREM

INVAP (Investigaciones Aplicadas - Applied Investigations) is an Argentine private high-tech company that builds mostly reactors, satellite parts (the only LatAm supplier of NASA), medical equipment and some defence applications such as radars, among others. The company built and delivered research reactors to Australia, Egypt, Algeria and Peru and currently has projects in Saudi-Arabia, Brazil and the Netherlands. Hence, there are many smart people in this company, further stressing the point that Argentina comes with quite a surprising amount of know-how. The headquarters is in Bariloche, Río Negro, and the Pilcaniyeu Technological Complex belongs to them. This complex is also where the uranium enrichment facility is located. But no worries, this is not in Bariloche, it’s 60 km to the east, in the middle of the steppe.

The company was founded in 1976 and shortly after, in 1980, it started working on CAREM (Central Argentina de Elementos Núcleares). It was presented to the public in 1984 and was therefore the first modular reactor design. In other words: Yes, the SMR (small modular reactor) is an Argentine invention. Che, I bet you didn’t know that? 💪🏻🇦🇷

But as we all know, developing and actually building these things is quite complicated. Due to financial issues, the project was stopped in the early 2000s after the crash of 2001, the corralito. But in 2006, it was reactivated and declared to be a project of national interested by the president Nestor Kirchner. The first concrete was poured in 2014 next to the Atucha NPP. Like with so many nuclear projects, things got more expensive, took longer, etc. The current state of affairs is that the construction works were halted in March because of the austerity imposed by the new government.

But at the same time, INVAP and CNEA reached an agreement to unite forces to get this project forward. The intent is to have a presentable reactor finished by 2030 and be able to export the model. In that regard, the Argentine SMR design is actually one of the most advanced and could capture a good market share if things work well. But with the current fiscal regime (whose necessity I fully understand), this timeline might be optimistic.

There are also plans to build a follow-up reactor, that will be a bit larger. But I guess that is something very unsure at the moment. Personally, I hope that the government understands that such a project is hard to impossible to advance without government support, at least outside the US. Since it is one of the most advanced SMR designs globally, the strategic importance of it is immense and could bring Argentina not only a great source of energy for remote towns (or mines!) in the future, but exporting SMRs would bring the country great revenues and would present Argentina as a country that has more to offer than a primary sector producing beef, grains and metals. Wouldn’t this be great? I hope Milei understands that.

Cutting the budget of the nuclear sector already affected it badly under Memen, and I don’t like to see a repeat of the story. All libertarianism aside, one needs to be a bit realistic here. Every ideology has its limits. On the other side, if they’d find an investor - great! But please no sell-out. With the US focussing on reindustrialization, I have the fear that there could be some interests to buy the CAREM project and bring it to the US. While I see nothing wrong with a foreign investor, it would be in the interest of Argentina that CAREM - once ready for market - is produced by an Argentine company in Argentina, to have the value creation where the investment came from. Milei has to be careful here.

Company overview: Blue Sky Uranium

While there are some other uranium projects in Argentina, I want to present the project that looks the most interesting to me and has a good potential of reaching production. Again, I’m seeing this from a geological/geopolitical standpoint, I am no expert on company finances. So before buying anything, double-check everything I’m writing here. No financial advice, do your own DD, etc. I am a shareholder of the company (who hasn’t paid for this, unfortunately) for a few years now. Average price: 0,15 CAD. Being totally honest here; know my bias.

Blue Sky Uranium (TSX-V: BSK) recently provided good news: The company published a PEA and found an investor to advance (and finance) their flagship Ivana project all the way to production. This is not only good for the company, it is also good for the country. The investor is Corredor Americano (COAM), an Argentine company belonging to Grupo America. I like to see that Argentine capital is available to finance Argentine projects. Many Argentines like to see that, too, and with quite a few examples of badly managed privatizations where foreign companies just sucked the blood out of Argentine assets, I have my sympathy for that thinking. On the other hand, if local investors are willing to invest, this can be seen as a big green flag for foreign capital. But let’s go into Blue Sky.

A district-scale deposit

Blue Sky’s projects are located in the mining-friendly province of Río Negro in Patagonia, the same province where INVAP is located as well. Therefore, the location is nuclear-friendly, too. The local geology is partially similar to Santa Cruz: Jurassic volcanics, partly covered by younger basalts, are the most important feature. Some older basement rocks exist as well and, of course, there is a lot of younger sedimentary cover. Like in Santa Cruz, Río Negro also hosts some gold-silver deposits, had an iron mine and some industrial minerals like salt and are mined today. Close to Bariloche, there’s also a natural oil spring (I need to go there one day…)

Key to the uranium mineralization here are the Jurassic volcanics: These rocks are located in the Somún Cura Massif, a geographic high located in the center of the province. Over the time, meteoric water (that’s a fancy way for geos to say rainwater), leached uranium from the volcanic material.

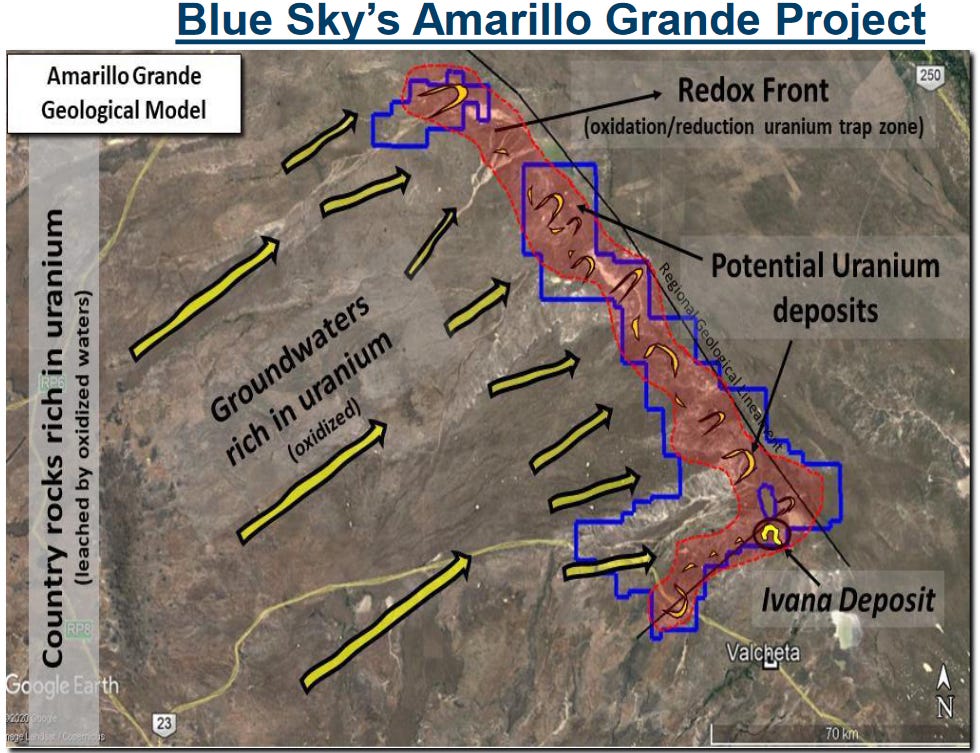

The Amarillo Grande (‘Big Yellow’) project comprises an east-west extension of some 140 km with Ivana being the main deposit in a setting that has some serious exploration potential. Like in Kazakhstan, Namibia or the US, such deposits are usually not alone and according to the company, that is also the case here. The first discovery the company made was in 2006 at Santa Barbara, proving the point that Río Negro hosts uranium. In 2011, the Ivana deposit was discovered. Quite a bad timing, that was the year of Fukushima. The company, however, survived the bear market in uranium and advanced the project. But this came at a cost for the shareholders: At a marketcap of ~17 million USD, the company has 278 million shares and 155 million warrants outstanding. The share price currently is at 0,06 CAD, and it didn’t perform greatly recently:

Blue Sky is part of the Grosso Group that is also involved in Golden Arrow Resources and Argentina Lithium & Energy. The Grosso Group is active in Argentina’s mineral sector since 1993 and its team was involved in the discovery of the Navidad silver deposit. They have extensive experience conducting work in Argentina, and that’s a big plus for me. This is not a company or team the learned how to spell uranium three weeks ago, as Rick Rule would say.

The PEA update in February gives a resource (indicated) of 19.7 Mt at 0,333 ppm U or 0,039 % U3O8 and an extra 5,6 Mt at 262 ppm U in the inferred category. Vanadium plays a minor role, with grades just above 100 ppm. To my taste, that’s relatively low grade, but still higher than i.e. Bannerman’s Etango deposit. According to the PEA, the AISC are only ~25 USD/lb U3O8 - offsetting the low grade using pre-screening of the ore. Another factor here is that the uranium is located very shallow (less than 25m) in unconsolidated sediment. The mine will actually be a sand or gravel pit, no blasting or crushing is needed, and this, of course, decreases the mining costs substantially.

The ore minerals are coffinite, a uranium mineral commonly formed when uranium-bearing groundwater interacts with organic matter in the sediment, and carnotite, a mineral that also contains vanadium (the yellow mineral shown before). The mined material passes a screener, separating ore from waste rock. This increases the feed grade by 4 times while reducing the mass by 77%. This means more uranium is leached from less ore, using fewer chemicals and energy. The technology for the screener was made by - you guessed it - INVAP, just 600 km down the Ruta 23. The total uranium recovery is 85%.

The NPV(8%) at a uranium price of 75 USD (I think that’s conservative) is around 230 million USD at an IRR of 38%, so the company currently trades at 5% of the NPV (17/315 million CAD). Capital costs to get this thing going are estimated to be 160 million USD. I might add here that these numbers come with the accuracy of a PEA and have been calculated under the ‘old regime’ with crazy import/export restrictions and currency gymnastics which are also best described as a boludez (Argie slang for stupidity, more or less). With Milei, that is changing. One needs to consider this, it could lower costs for bringing things into production. RIGI however (the new incentive program for large investments over 200 million USD) would not apply here. But perhaps they can fiddle around the numbers in the DFS to profit from RIGI, if you know what I mean. ;)

Due to the huge exploration potential (again, 145 km strike length), the cost per pound could be further reduced with more resources added or, eventually, when/if satellite projects come into production and a hub-and-spoke model is introduced, similar to what UEC is doing in Texas, for example.

What I also like about the project is the location. The nearest settlement (and practically the only one) is Valcheta, a small village with a few thousand inhabitants. The abovementioned Ruta 23 passes along the deposit, connecting Bariloche in the west with San Antonio del Oeste, a small port town, and Viedma, the province’s capital, in the east. Along the RN23, there is a railway that was reactivated a couple of years ago. Due to the increased activity in Vaca Muerta, there are plans to build extra oil and gas infrastructure (such as an LNG terminal) in Río Negro. Therefore, energy supply and accessibility is no problem. The area is flat, low altitude and besides the terrible wind so common in Patagonia and perhaps a bit of snow in winter, work can be conducted all-year round. Río Negro, unlike its southern neighbour Chubut (check out my boots on the ground report from there), is open for mining.

Another aspect I like a lot is that according to Argentine law, the nuclear industry needs to buy domestic uranium first if it is available. This means Blue Sky already has a customer with a demand of roughly half a million pounds annually - about a third of Ivana’s planned production.

The Deal

In early June, Blue Sky announced a proposed transaction with Corredor Americano (COAM) to advance the Ivana deposit to a feasibility study and production if the DFS looks good. Key highlights are:

COAM can earn up to a 50% indirect interest in the Property by spending up to US$35M and advancing Ivana through to completion of a feasibility study, and to drill key exploration targets located in adjacent areas of the Property.

Following a positive feasibility study, COAM can earn an additional 1% upon its decision to fund the capital cost of the Project and further 29% interest in funding 100% of the estimated capital costs to achieve commercial production.

See the original news release here.

In short, if this deal gets signed, Blue Sky could bring the deposit to production without further diluting shareholders (well, except the 155 outstanding warrants of course), plus further upside from exploration.

On one side, this means the company doesn’t need to issue more shares to finance the project in the future. On the other side, at an average exercise price of the warrants around 0,19 CAD and a current share price around 0,06 CAD, it is the question if this good outlook results in an increase in share price, leading to the exercise of these warrants and hence further dilution. When I look at the chart, I see much upside potential and likely a bottom, especially if (when) the uranium price goes up again and/or the situation in Argentina improves. In other words, a higher likelihood that the warrants get exercised. One needs to be aware of that.

A bit more leverage: Blue Sky also has some properties in Chubut. Not much happening there at the moment. But since Chubut hosts some former uranium mines, the potential there is high and if Chubut opens for mining, Blue Sky is in an excellent position to profit from that. The company’s claims there look interesting to me. But this is speculative upside potential. Just yesterday, the company announced two new exploration projects, one in Neuquén and the other in Mendoza. The company will need to raise some money for early-stage exploration there, but I guess that’s well spent.

Summary

I think Argentine mining stocks had (and still have) a hard time, besides some of the very prominent copper stories. Blue Sky, to my mind, flies a bit under the radar and suffered from the decade-long bear market and mess of the last governments Argentina had. The stock is quite diluted and all the outstanding warrants worry me a bit. Also, many investors are still hesitant to come to Argentina, which is understandable. Milei needs to present more reform progress, but with the recent pass of the Omnibus bill, progress is being made, and I am very optimistic.

Personally, I am willing to take the risk of further dilution from the warrants at this low share price. With the new investor, the financing risk is very low and the surrounding local factors as well as the bull market for uranium (that just started in my opinion) provide further upside potential. And naturally, as a geo, I am amazed by the potential size of this uranium district. I am pretty sure Ivana’s sisters are attractive as well. ;-)

I hope this article gave you a good overview about Argentina’s uranium and the nuclear industry of the country, as well as a basis for further research on Blue Sky. Please leave me a like or, if you’re new here, a subscription.

Hasta la próxima!

Great article!

What AI template/theme are you using for this photos?

Excellent write-up. I really enjoy reading it.

I follow the uranium sector and Argentina but never considered blending them.

I prefer to express commodity themes with direct exposure to the commodity, and LEAPS calls on the most liquid majors. In this way, I get the upside of junior miners with the downside of major miners.

This is not to say small caps do not bring asymmetric opportunities. However, understanding geology is a must. Without knowing how to read the intricate geological reports, we have no real edge.